Towards A Stable Economy And Politics

Towards a Stable Economy and Politics[1]

Nadeem Ul Haque, Vice-Chancellor, PIDE and Raja Rafi Ullah, Research Fellow, PIDE

-

Context to the Knowledge Brief

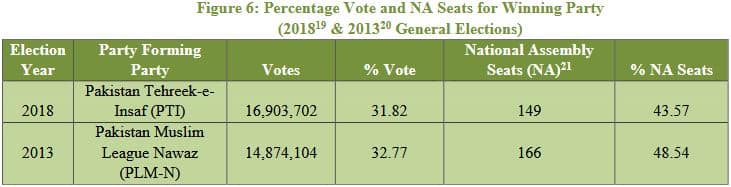

Pakistan throughout its history has seen regime changes from more democratic to more authoritarian and vice versa. This has meant that the country’s political and social landscapes have remained volatile and unstable. Many economists argue that this instability has partly contributed to the stifled and irregular growth patterns in the country. The average GDP growth rate has been irregular from decade to decade, with an overall long-run downward trend (See Figure 1). If political stability is a prerequisite to sustained rapid economic growth, have then stable non-democratic regimes been more successful in Pakistan at spurring high growth and leading to higher standards of living? Surely, such simplistic viewpoints are mere rhetoric. A study published in The Pakistan Development Review in 2016 that used data from 1960-2013 for 92 countries including Pakistan found a negative relationship between Human Development Index (HDI) and prevalence of authoritarian institutions.[3] Furthermore, experts argue that for democratic regimes to lead to sustained rapid economic growth, the democratic institutions must be allowed to mature over time through successful democratic transfers of power.______________________________[1] This Knowledge Brief is a follow-up to a webinar organised by PIDE titled, “Towards a Stable Economy and Politics” on May 9, 2020. Moderated by the VC, PIDE, Dr. Nadeem Ul Haque, the speakers included Wasim Sajjad (lawyer, Politician and Former Senate Chairman), Irfan Qadir (Former Attorney General of Pakistan), and Hasan Askari Rizvi (Pakistani Political Scientist and Military Analyst).[2] Data Source: Pakistan, World Development Indicators, World Bank, 2020[3] Khan, Batool, and Shah (2016), The Pakistan Development Review, 55(4).

If political stability is a prerequisite to sustained rapid economic growth, have then stable non-democratic regimes been more successful in Pakistan at spurring high growth and leading to higher standards of living? Surely, such simplistic viewpoints are mere rhetoric. A study published in The Pakistan Development Review in 2016 that used data from 1960-2013 for 92 countries including Pakistan found a negative relationship between Human Development Index (HDI) and prevalence of authoritarian institutions.[3] Furthermore, experts argue that for democratic regimes to lead to sustained rapid economic growth, the democratic institutions must be allowed to mature over time through successful democratic transfers of power.______________________________[1] This Knowledge Brief is a follow-up to a webinar organised by PIDE titled, “Towards a Stable Economy and Politics” on May 9, 2020. Moderated by the VC, PIDE, Dr. Nadeem Ul Haque, the speakers included Wasim Sajjad (lawyer, Politician and Former Senate Chairman), Irfan Qadir (Former Attorney General of Pakistan), and Hasan Askari Rizvi (Pakistani Political Scientist and Military Analyst).[2] Data Source: Pakistan, World Development Indicators, World Bank, 2020[3] Khan, Batool, and Shah (2016), The Pakistan Development Review, 55(4).

1.1. Institutions

Mature representative institutions are a key ingredient to sustained economic growth[4]and same is true for state institutions such as the executive, parliament, bureaucracy and the judiciary. Unfortunately, Pakistan throughout its history has maintained non-representative state institutions that serve to maintain the status quo. This in part is due to the colonial[5] setup of the state machinery that Pakistan inherited upon independence. Having said that, all cannot be attributed to historical contingency; there are systematic issues that if addressed can help bring about stable and representative institutions that drive sustained rapid economic growth.

1.2. Governance

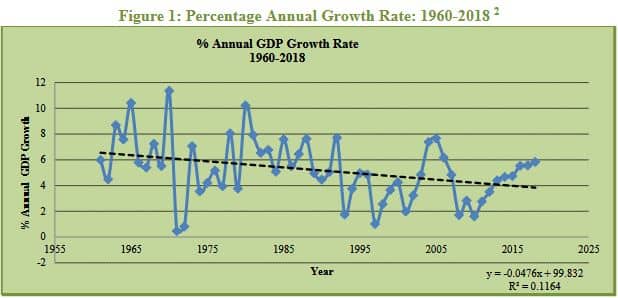

Governance issues have typically impeded economic growth and investment in the country. Pakistan has too many layers of government that many times have hampered the growth of private enterprise in the country. This view is echoed in Pakistan’s ranking on World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGIs). Pakistan has the lowest percentile rank among its peer countries[6] on 3 out of 6 WGI indicators: Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Rule of Law. Of the three remaining indicators on Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality and Control of Corruption only Bangladesh is ranked lower. [7] (See Figure 2) Given the scenario described above, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) brought together experts[9] for a webinar to discuss the issues. A summary of the questions addressed in the webinar is presented below:____________________________[4] Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), Chapter 5, Why Nations Fail.[5] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2017), Looking Back: How Pakistan Became an Asian Tiger by 2050.[6] WGI Indicators (2018) comparison of 4 South Asian Countries: Bangladesh, India, Pakistan & Sri Lanka.[7] Worldwide Governance Indicators (2018), World Bank, info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi[8] Worldwide Governance Indicators (2018), World Bank.

Given the scenario described above, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) brought together experts[9] for a webinar to discuss the issues. A summary of the questions addressed in the webinar is presented below:____________________________[4] Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), Chapter 5, Why Nations Fail.[5] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2017), Looking Back: How Pakistan Became an Asian Tiger by 2050.[6] WGI Indicators (2018) comparison of 4 South Asian Countries: Bangladesh, India, Pakistan & Sri Lanka.[7] Worldwide Governance Indicators (2018), World Bank, info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi[8] Worldwide Governance Indicators (2018), World Bank.

2.1. Is Politics in Pakistan Dominated by Dynasties/Families? Can a “Common Person” Enter Politics?

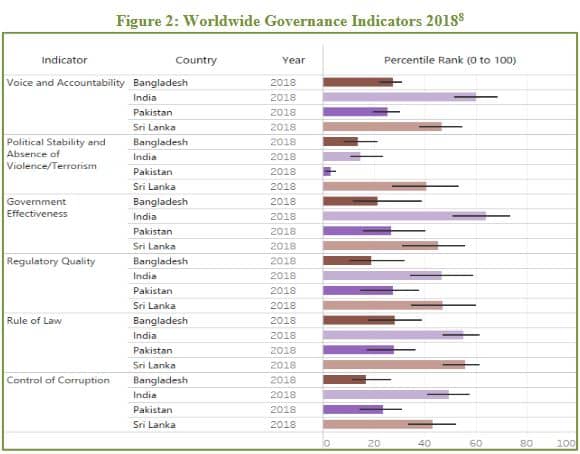

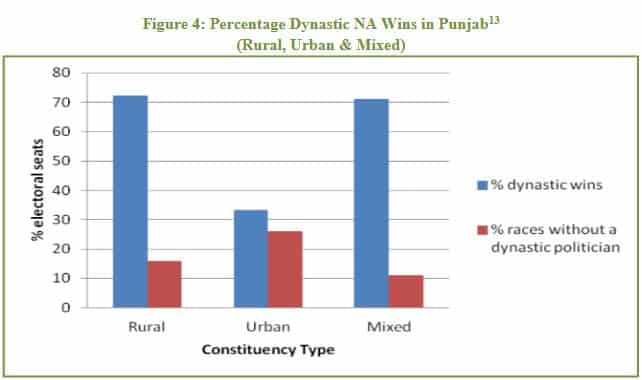

The politics in Pakistan is characterised by a dilemma where despite there being hotly contested elections the political landscape is still dominated by families and dynasties. Those who are not part of existing powerful political families/dynasties have low chances of both entering politics and being successful in elections. Cheema et al. (2013) investigated this question of dynastic politics using data from Punjab and found that from 1985-2008 on average two-thirds of elected national-level legislators (MNAs) and about half of all MNA candidates from MNA constituencies in Punjab were dynastic. [10] (See Figure 3)  The data points towards the fact that there is a high incidence of dynastic politicians (also known as electables) who have permeated the system down the level of individual constituencies. Although Cheema et al. (2013) have used data from Punjab only, the situation in other provinces in Pakistan can be assumed to follow similar patterns. Comparatively speaking on a regional level, the percentage of dynastic legislators in the national assembly observed by Cheema et al. (2013) is almost twice the percentage of such legislators in the Indian National Assembly/Lok Sabha. [12]Despite there still being a high incidence of dynastic politics in Pakistan, the numbers have declined slightly in urban areas over the past few decades. Whereas in non-urban areas the problem still remains pronounced. And we should remember that the distribution of constituencies has not been aligned with the new census._________________________[9] See back-end of the document for list of webinar panelists.[10] Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 1[11] Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 2[12] French, Patrick. (2011). Quoted in Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 2

The data points towards the fact that there is a high incidence of dynastic politicians (also known as electables) who have permeated the system down the level of individual constituencies. Although Cheema et al. (2013) have used data from Punjab only, the situation in other provinces in Pakistan can be assumed to follow similar patterns. Comparatively speaking on a regional level, the percentage of dynastic legislators in the national assembly observed by Cheema et al. (2013) is almost twice the percentage of such legislators in the Indian National Assembly/Lok Sabha. [12]Despite there still being a high incidence of dynastic politics in Pakistan, the numbers have declined slightly in urban areas over the past few decades. Whereas in non-urban areas the problem still remains pronounced. And we should remember that the distribution of constituencies has not been aligned with the new census._________________________[9] See back-end of the document for list of webinar panelists.[10] Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 1[11] Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 2[12] French, Patrick. (2011). Quoted in Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 2  In comparison to urban politicians, dynastic politicians in cities are 40 percent points less likely to win their constituencies. (See Figure 4) Furthermore, the number of elections that don’t have any dynastic politician running for office is 10 percent points higher in urban areas as compared to rural areas. (See Figure 4)Despite the observed decline in urban areas, familial political dynasties still wield significant power in Pakistan and continue to maintain the status quo. Having said that, certain policies if implemented correctly can trigger transformation and make entry of more non-dynastic politicians into the system possible. Adjusting constituencies in line with the censuses will allow increasing urbanisation to open out the political landscape. The hold of dynasties will weaken.Strengthening and facilitating the local government system by holding periodic elections. Barriers to entry in local elections for non-dynastic politicians are less than in elections at higher levels i.e. provincial and national.Furthermore, many countries in the world have term limits on “one or more executive and elected positions. Pakistan no longer has any term limits on any directly elected position. We only have term limit for the post of the President which at best can be described as only a ceremonial position under the current constitution arrangement. Introducing term limits for positions such as the “Prime Minister, Minister or even membership of parliament” will allow for new people to come into the system.[14]

In comparison to urban politicians, dynastic politicians in cities are 40 percent points less likely to win their constituencies. (See Figure 4) Furthermore, the number of elections that don’t have any dynastic politician running for office is 10 percent points higher in urban areas as compared to rural areas. (See Figure 4)Despite the observed decline in urban areas, familial political dynasties still wield significant power in Pakistan and continue to maintain the status quo. Having said that, certain policies if implemented correctly can trigger transformation and make entry of more non-dynastic politicians into the system possible. Adjusting constituencies in line with the censuses will allow increasing urbanisation to open out the political landscape. The hold of dynasties will weaken.Strengthening and facilitating the local government system by holding periodic elections. Barriers to entry in local elections for non-dynastic politicians are less than in elections at higher levels i.e. provincial and national.Furthermore, many countries in the world have term limits on “one or more executive and elected positions. Pakistan no longer has any term limits on any directly elected position. We only have term limit for the post of the President which at best can be described as only a ceremonial position under the current constitution arrangement. Introducing term limits for positions such as the “Prime Minister, Minister or even membership of parliament” will allow for new people to come into the system.[14]

2.2. Does the Electoral System in Pakistan Need Reform?

Free and fair elections on periodic basis are one of the most effective ways through which a country’s institutions mature over time. Pakistan for the first time in its history has had two parliaments complete the constitutional 5 years without a mid-year election (2008-2013 and 2013-2018). This is a welcome sign, but the electoral system in Pakistan needs to be reformed to accelerate the process of building strong democratic systems in the country.

- Currently as it stands both national and provincial assemblies remain in place for five years unless parliament is dissolved earlier. The consensus among our eminent speakers was that this was perhaps too long. Recent experience has shown that the parliament becomes contentious, fragmented and often dormant. The pressure of elections which is supposed to keep the government on its toes is somewhat distant in a 5-year term and contributes to this lack of cooperation between the political parties. Our eminent speakers agreed that there was a need to reduce the constitutional term of the parliament at provincial and federal levels to 4 years.

- Our speakers also felt that there was a need for more frequent elections rather than the once in 5-year pattern that we currently have. Everything, the senate, the president and all levels of government are decided in one election. The Federalist Papers noted that in making the US Constitution, it was carefully deliberated to set up a system with differing terms for president, the House of Representatives, the senate, the state and local governments to ensure that elections happened every year for some level of government. The panel felt that perhaps it was time to consider direct senate elections as opposed to the current indirect method.

- The panel also agreed that there was an urgent need to develop a local government system with a four-year term and to allow the election cycle of that to differ from the national and provincial cycles. With the senate, provincial, local and national elections, regular elections will keep a barometer on all parties on a continuing basis.

- The election system too was reviewed, and 3 issues were discussed:

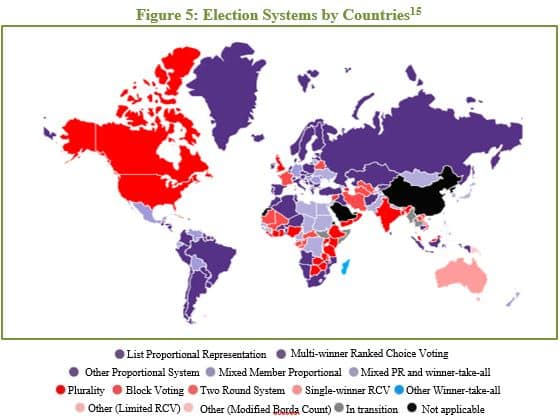

- “First past the post” (FPTP) also known as “Plurality” system is the oldest election system in the world and was also adopted by Pakistani. However the FPTP system is used only by a minority of countries mostly the US, UK and a few former British colonies. (See Figure 5) Even Pakistan has accepted a proportional system for women seats.

_______________________[13] Cheema, Ali., Javaid, Hassan., and Naseer, Farooq (2013), Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications, IDEAS, Pg. 5.[14] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2017), Designing Democracy and What is the PM Term?, Development 2.0 __________________________[15] Electoral Systems Around The World, FairVote.org

__________________________[15] Electoral Systems Around The World, FairVote.org

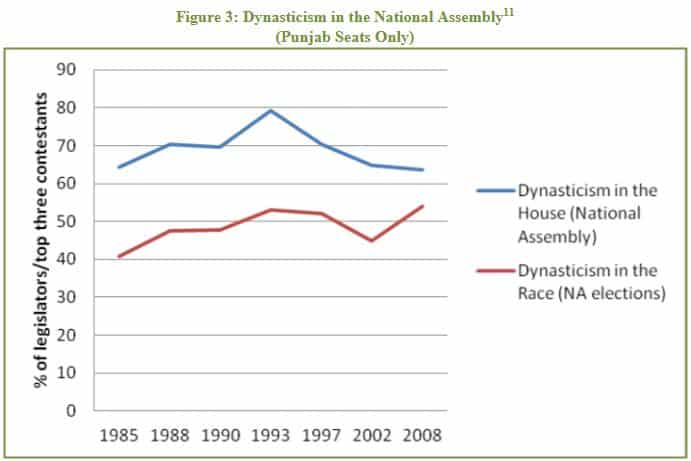

- The FPTP system has also produced majority governments despite the parties forming governments earning less than one-third of the total vote. For instance, in the last two general elections, PML-N (2013) and PTI (2018) won 33 percent and 32 percent of votes respectively and yet were still able to form majority governments by bringing in independents and regional parties MNAs. (See Figure 6) Our panel felt it was time to examine other systems to allow more representation and workable governments to emerge.

- The Articles 51[16] and 106[17] of the constitution lay down the mechanisms for allotment of seats for women and minorities in national and provincial assemblies respectively. Currently as it stands the seats are allocated proportionately based on election results among the parties. Some of our panelists argued that although this allocation of reserved seats adds diversity through inclusion in the legislatures, the process also distorts the system. Furthermore, since the allocation is made from the nomination lists provided by the parties, it leaves women and minority candidates at the mercy of the whims of their parties’ leaderships. Perhaps there is a need to devise a system that includes more direct forms of election on these reserved seats. [18]

- The rules pertaining to definition of what constitutes a political party are such that growth of non-representative political parties is encouraged. The Chapter XI (sections 200-213) of Elections Act 2017[22] specifies rules for definition, formation and functioning of political parties. The rules specify that any “body of individuals or association of citizens” can form a political party and that only 2000 registered members are required for formation and enlistment of a political party. Most of our eminent panelists agreed that rules including this membership threshold is too low and encourages the growth of splinter/fragmented parties who don’t necessarily reflect the needs and the desires of the electorate at-large. Perhaps there is a need to devise rules that lead to representative political parties by increasing the number of registered party member who include both active members and those who make significant contributions to party funds.

- Furthermore, the laws pertaining to intra-party elections as specified in section 208 of Elections Act 2017[23] are not elaborate enough to result in true representative intra-party democracy. On top of that, the Election Commission is often lax in enforcing these rules and most often the intra-party elections are exercises carried out to fulfill formalities rather than being carried out in the spirit of promoting intra-party democracy. The result is that existing dynastic and personality based power asymmetries are reinforced in most political parties in Pakistan.

- The asymmetries of power are further strengthened when those party members who are lucky enough to get party tickets and enter the parliament, are then again unable to voice any opinions other than those dictated by the party center. The 14th Amendment to Constitution[24] has fundamentally made it impossible for members to vote against party-lines in the legislature.

__________________________[16] Article 52 of Constitution, Pakistanconstitutionlaw.com[17] Article 106 of Constitution, Pakistanconstitutionlaw.com[18] Shah, Waseem. (2018), Mechanisms for filling reserved seats seen as flawed, DAWN Newspaper[19] General Elections 2018, Election Commission of Pakistan.[20] General Elections 2013 Report, Election Commission of Pakistan.[21] Figures include proportionally allocated reserved seats for women and minorities.[22] Elections Act 2017.[23] Elections Act 2017.[24] 14th Amendment, Pakistanconstitutionlaw.com

2.3. Does Pakistan have too Many Federal Ministers/Ministries?

- In Pakistan currently there are 51 current members of the Federal Cabinet Division including 31 Cabinet Ministers, 5 Advisors to the Prime Minister and 15 Special Assistants to the Prime Minister.[25] The question is that whether Pakistan actually needs these many federal ministers, or should the size of the cabinet be reduced to encourage simplicity particularly given that the 18th Amendment and the NFC Award have significantly devolved key functions to the provinces. Although it is true that the number of ministers at the federal level is below the maximum stipulated by the 18th amendment to the constitution; yet there are too many ministries that could instead be merged into other ministries. For instance, what is the point of having a separate petroleum minister when there is already an energy minister? Or why have separate federal ministries for health, education and food security when these functions have been devolved to the provinces? [26]

- Some of our eminent panelists recommended reducing the size of cabinet through mergers and proper streamlining. This reduction was advised particularly keeping in mind that in addition to the ministers, Pakistan also has an extensive bureaucracy at federal level consisting of secretaries that wield substantial power. The ministers combined with the bureaucrats add to the layers of government that fosters confusion, rent-seeking behaviours and increased regulatory control. All this acts to stifle private investment and reduces the ease-of-doing-business. In such stead, the policy of excessive ministerial appointments to accommodate coalition parties in government needs to be revisited.

2.4. What about the Question of Reforming the Civil Service of Pakistan?

- Pakistan from its very beginning inherited a colonial style civil service structure that is extractive and non-representative. [27] Having said that, incessantly pointing out that the bureaucratic structures are inefficient and corrupt does not serve constructive purposes. Perhaps we need to realise that self-interested profit-seeking is one of the basic human psychological traits. An alternate way of addressing the problem could be by creating innovative incentive structures that promote efficiency and performance in the civil service.[28] This would require careful drafting of performance contracts that reward high levels of effort through measuring observable indicators. Having said that, drafting of effective incentive contracts is a specialised skill, which if carried out correctly holds the key to solving many problems that plague the civil service in Pakistan.[29]

- For effective civil service reform, perhaps the need of the hour is to look at a micro-level and understand what drives day-to-day behaviour of civil servants and work backward from there to formulate policy interventions. [30]________________________[25] Cabinet Division, cabinet.gov.pk[26] Mehboob, Ahmed. (2018), How Big Should the Cabinet Be?, DAWN Newspaper.[27] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2017), Looking Back: How Pakistan Became an Asian Tiger by 2050.[28] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2007) , Why Civil Service Reforms Don’t Work, PIDE, Pg. 16.[29] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2007) , Why Civil Service Reforms Don’t Work, PIDE, Pg.16.[30] Haque, Nadeem Ul et al. (2006), Perception Survey of Civil Servants: A Preliminary Report.

2.5. How can the Legislature be Empowered?

An empowered strong legislature including the parliament needs to complement the executive branch in policy making. Currently, the parliament as a body is not strong and doesn’t guide bulk of the policy making.

- Our panelists agreed that although having parliamentary approval as a prerequisite for each and every policy decision would cause excessive delays, the parliament still needs to grow and mature as an institution. Recently, parliamentary standing committees on various subject matters have added to the empowerment and relevance of the parliament. This process can be furthered by adding periodic parliamentary review in the TORs of such committees on matters that fall under their mandate.

- A balanced equilibrium between the three pillars of the state i.e. executive, legislature and judiciary often lead to systems that are conducive to stability and hence facilitate economic growth. Important ingredients to such equilibrium are constitutional frameworks that allow for cross-institutional checks on power, but also at the same time ensure that institutional overreach is limited. Perhaps it is time to look at introducing reforms such as judicial reforms to make sure that while acting as an important institution for checking the power of both the legislative and legislature, the judiciary doesn’t stand in the way of policy making and issues of legislative and executive concern that require immediate action.

- Our panelists also mentioned that the interplay between the executive and the parliament also needs to be examined. In Pakistan, even in democratic setups, the quench for unchecked power to dictate policy is as such that the executive (usually the Prime Minister and his close group of ministers) deliberately weaken the parliament when it comes to having a voice in policy making.[31] One example of such executive overreach is the 14th Amendment to the Constitution which reinforced strict party discipline essentially meaning that those ruling party members who oppose executive decisions in parliament are constitutionally liable to being disqualified from the house and have their party membership cancelled.

2.6. How can Technical Processes be Insulated from Politics?

Technical processes such as management of public health, managing the energy sector and formulating an effective Public Sector Development Program (PSDP) are tasks that require level of expertise that go beyond political dictation. In Pakistan elected politicians, particularly those who are vested with some sort of executive power often interfere in ways that impede evidence-based policy formulation and implementation of technical processes. Furthermore, there is a common perception among politicians and public at-large that ‘technocrats’ have harmed the democratic system since most dictators brought an entourage of technocrats into government. However, this rhetoric and complementary aversion of politicians to technocrats is misleading, because in principle Pakistan has never had technocrats brought into policy making through a rigorous selection process. Those technocrats who have ended up in positions of authority under dictators have often come about because of cronyism rather than as a result of selecting the best suited persons for the jobs. [32]Our panelists agreed that in most mature democracies it is not the ministers and ones with executive power that dictate specifics of policy formulation which requires a level of expertise. If one was to draw parallels to how a corporation is run; the ministers in mature setups act as board members who give policy direction but are not involved in either day-to-day operations or formulation of policies that require specialised skills and qualifications. A good place to start in Pakistan could be to stop promoting rhetoric that “lumps all manner of skilled professionals into one vague category” i.e. ‘technocrats’.[33] Skilled professionals are part of almost all mature democratic systems and play a pivotal role in efficient service delivery and don’t act as an automatic antithesis to democratic elected politicians._______________________[31] Haque Nadeem Ul. (2018) , Imperial Democracy, Development 2.0.[32] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2017), Why Do Politicians Hate Technocrats?, Development 2.0.[33] Haque, Nadeem Ul. (2017), Why Do Politicians Hate Technocrats?, Development 2.0.

REFERENCES

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Publishing Group.Ahmed, M. (2018 Oct. 12). How big should the cabinet be?, DAWN, Column.Cabinet Division (2020). Available at: <cabinet.gov.pk>Cheema, A., Javaid, H. and Naseer, F. (2013). Dynastic politics in Punjab: Facts, myths and their implications. IDEAS.Databank.worldbank.org. (2020). World development indicators | Databank.Election Act and Election Rules, Election Commission of Pakistan. Available at: <https://www.ecp.gov.pk/frmGenericPage.aspx?PageID=3111>Election Report (2013). Election Commission of Pakistan. Available at: <https://www.ecp.gov.pk/ frmGenericPage.aspx?PageID=3050>Electoral Systems Around The World, Fairvote (2020). Fairvote.French, P. (2012). India: A portrait. (Vintage Departures).General Elections (2018). Election Commission of Pakistan. Available at: <https://www.ecp.gov.pk/ frmdynamicnotifications.aspx?id=17>Haque, N. (2007). Why civil service reforms do not work. SSRN Electronic Journal.Haque, N. (2017). Looking Back: How Pakistan became an Asian tiger by 2050 (1st ed.). Karachi: Kitab (Pvt.) Limited.Haque, N. (2020). Blog. Development 2.0. Available at: <http://development20.blogspot.com/>Haque, N., Din, M., Khawaja, M., Malik, W., Khan, F., Bashir, S. and Waqar, S. (2006). Perception survey of civil servants: A preliminary report. The Pakistan Development Review, 45(4II), pp. 1199–1226.Khan, K., Batool, S., & Shah, A. (2016). Authoritarian regimes and economic development: An empirical reflection. The Pakistan Development Review, 55(4I-II), pp. 657–673.Shah, W. (2018). Mechanism for filling reserved seats seen as flawed. Dawn Newspaper. https://www.dawn.com/news/1417406.Worldwide Governance Indicators (2018). Available at: <https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/>